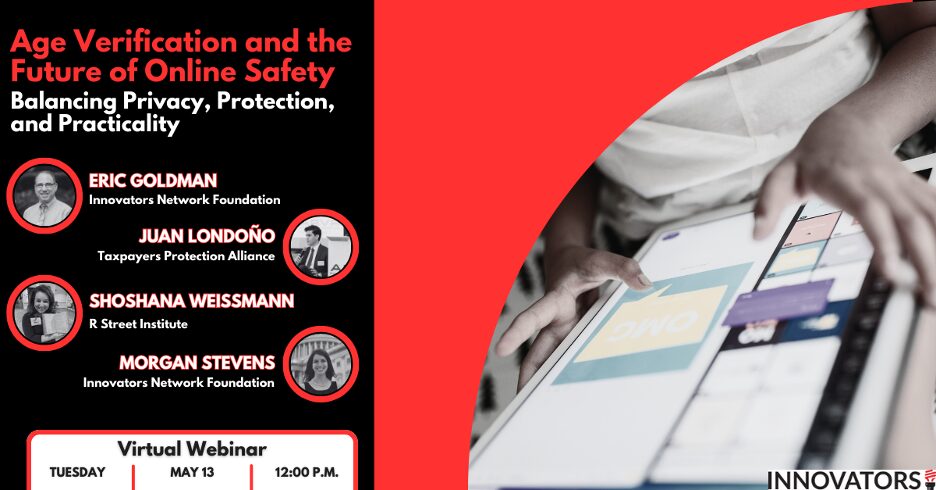

The Innovators Network hosted a webinar, Age Verification and the Future of Online Safety, featuring an expert panel including:

- Eric Goldman, Professor at Santa Clara University School of Law and Co-director of the High Tech Law Institute;

- Shoshana Weissmann, Director of Digital Media and Resident Fellow of Technology and Innovation at the R Street Institute;

- Juan Martín Londoño, Chief Regulatory Analyst at the Taxpayers Protection Alliance; and

- As moderator, Morgan Stevens, Privacy Fellowship Manager at the Innovators Network.

The panelists discussed the privacy and security risks of age verification and the broader implications such mandates pose to an open internet.

How Online Age Verification Differs from the Offline World

The panel opened with what Eric Goldman called, “the granddaddy of internet law questions”: What makes the internet unique, special, and different, and how should that shape regulation?

Juan Martín Londoño observed that, unlike verifying ages online, offline age authentication is often fleeting. Consumers show their ID to an employee, who simply reviews and returns it. The offline review process doesn’t leave a record as to where the consumer has been, what they’ve reviewed, or what they ultimately purchased.

Eric echoed this, explaining that offline age authentication, whether through visual inspection or document review, requires no record of the authentication, electronic mediation, or data storage. He also noted that online age authentication essentially creates checkpoints on the internet that prevent consumers from interacting with online spaces without first providing proof of age. Further, unlike offline spaces, such as a bookstore that allows anyone to browse without cost or credentials, online publishers have to pay to authenticate users before knowing if the consumer will be valuable to them.

Privacy, Security, and the Limits of Technology

Turning to the privacy and security risks of age verification, Juan emphasized that treating these concerns as purely technical problems ignores the reality that bad actors can innovate as quickly as good actors. As a result, advances in cryptography or privacy-preserving technologies will not necessarily keep consumer data safe. Moreover, less invasive technologies to protect children online, such as parental controls, already exist and can be implemented without compromising users’ privacy.

Eric challenged the popular notion that emerging technologies, such as zero-knowledge proofs, can mitigate, if not eliminate, the privacy and security risks of age authentication. In theory, zero-knowledge proofs, which enable publishers to allow users through checkpoints without transferring any private or sensitive information to them, reduce privacy risks. However, in practice, zero-knowledge proofs simply shift the authentication burden and location of collected data from the publisher to another entity in the system. Further, there’s still significant value in knowing whether a consumer is able to pass through an age gate. Removing the burden of age authentication from online publishers doesn’t make the data any less valuable as a target.

Ultimately, even if zero-knowledge proofs offer a technically feasible means of authenticating age in a way that mitigates privacy issues, a mandate to use this technology undoes its privacy benefits. Enforcers of an age verification law will not simply take a company’s word that they verified ages. Regulated entities would need hard evidence showing their age verification tools actually work, which necessitates the collection and preservation of data necessary to prove compliance. Even if age verification tools can mitigate privacy risks, that alone is not sufficient reason to mandate that they be used on all consumers seeking to access online services, regardless of whether age-related risks exist.

Eric also cautioned that age verification infrastructure could eventually be co-opted to control access to information. What some policymakers pitch as a tool to protect children could evolve into a system of digital checkpoints used to monitor or restrict who can access online content.

Finally, Eric pointed out how normalizing face scans or document reviews as prerequisites for online access is a troubling trend, especially for kids. It sends a signal that they must trade personal data for internet access, setting a precedent that could erode privacy expectations more broadly.

Who Should Handle Age Checks: App Stores or Devices?

Some current proposals shift responsibility for age verification to app stores or device makers. However, panelists cautioned that this raises new problems.

Shoshana Weissmann cautioned that such requirements might lock families into certain device ecosystems, eliminating flexibility and limiting device reuse. She also warned that they would force every app—even those with no obvious age-related risks—to have the infrastructure necessary for compliance. While large companies have the resources necessary to build the infrastructure, small businesses would likely have to divert resources away from hiring, research and development, or other areas critical to growth in order to comply. In fact, according to one study published after this panel, if every state enacted such a law, it could collectively cost small businesses with apps $70 billion at the low end and $280 billion near the high end.

Juan noted that legal liability and private rights of action in some state proposals could incentivize authenticators to over-verify users’ age. Rather than checking once, authenticators may have to continuously monitor users’ activities to estimate their ages and avoid questions about compliance.

Finally, Eric argued that localizing the authentication process to app stores or devices is an incomplete and unnecessarily balkanizing form of age authentication. It overlooks large swaths of the online ecosystem, ignores the reality that many families share devices, and creates monopolistic advantages for platforms already holding vast amounts of data. These gatekeepers could then essentially tax the rest of the internet by monetizing age verification services.

Accessibility and Global Impacts

Towards the end of the panel, the audience raised questions about accessibility concerns. In response, Shoshana pointed out that many consumers on the internet don’t have the required identification or technology, such as cameras, to provide proof of their ages, which would essentially prevent them from accessing content on the internet, even if they can pass through age gates. She also noted that many kids don’t have government-issued IDs to use during the age verification process. In some states, it’s difficult to obtain a photo ID that isn’t a driver’s license. Even birth certificates pose challenges when a child’s parents are divorced, guardianship is unclear, or parents aren’t present. Juan added that U.S.-based IT systems or authenticators likely wouldn’t be able to process foreign birth certificates and non-English names, such as those with accents or multi-part surnames, as well as common identification methods or names in the United States, creating additional access barriers to content on the internet.

Eric stressed that automated, scalable systems would still need manual alternatives for users with disabilities or in case of errors. Adding a manual system would likely be costly and hard to scale for authenticators. Moreover, many users could likely find workarounds to the systems, such as buying verified devices or using fake identification, further undermining the effectiveness of age verification mandates.

What’s Next: A Constitutional Challenge

The panel concluded by previewing a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton, which has since been decided. In that case, the Court upheld a Texas law requiring age verification for access to online content deemed harmful to minors. The Court applied intermediate scrutiny and found the law constitutional because it imposed only an incidental burden on adults’ access to protected speech. While technology has advanced since the Court struck down mandatory online age authentication requirements in the 1990s and early 2000s, the core constitutional concerns around free expression and privacy remain deeply contested. As Eric noted, the internet has evolved, but the constitutional questions that matter most have not.

Conclusion

As Eric explained, age verification is “the biggest threat to the internet that we’re facing.” Rather than enacting these sweeping mandates, policymakers should pursue balanced approaches that empower parents, protect users’ rights, and avoid unintended harms to digital innovation and access.