Last week, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) hosted a listening session as part of its ongoing work on child safety online. This week, the Senate Judiciary Committee hosts a hearing on Big Tech and the Online Child Sexual Exploitation Crisis. In both discussions, policymakers were urged to make app stores liable for providing parental notice when a child wants to download an app. The problems with this idea are that (1) to the extent it requires age verification, it would likely be unconstitutional; (2) it would supplant parents with government as the main decisionmaker for kids on app stores; and (3) it could only make existing parental control functions worse, not better.

During the NTIA session, ACT | The App Association’s President, Morgan Reed, outlined the principles that are important to small app companies as government agencies and Congress contemplate intervention. Chief among them is ensuring that any government regime enables flexible approaches to parental consent and that the existing Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act’s (COPPA’s) verifiable parental consent (VPC) regime is a difficult and overly constrictive way of handling it. For years, App Association members have called for a more realistic and flexible approach to VPC, because imposing such onerous requirements on parents makes it difficult for child-facing apps. Unfortunately, some stakeholders now want Congress to build on the awkward governmental layer between parents, kids, and smart devices with a new liability regime imposed on app stores. Specifically, they are proposing that Congress enact a law requiring app stores to provide or facilitate notice to parents if their child wants to download certain apps. App stores already provide these notifications, so something else is going on, and it’s worth taking a closer look at the idea and the problems it would create.

Categorizing apps. In order to provide parents with options when a child wants to download an app, segmenting by age appropriateness is used as a predicate to trigger notice. App stores categorize apps according to the appropriate age of an app’s intended audience. For example, Apple’s App Store provides three age-based categories for kids’ app developers: 5 and under, 6 – 8, and 9 – 11. Apple further categories apps for older audience as either for 12+ or 17+. Apps used for dating, gambling, or that provide unrestricted web access in an embedded browser are examples of apps that fall into the 17+ category. Most other app stores follow the International Age Rating Coalition (IARC) framework, which various regions across the globe adapt to fit local norms and laws. For example, the North American IARC member, Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB), uses the following categories: E for Everyone (all ages), E10+ (for ages 10 and over), T (for teens 13 and over), M (for mature audiences 17 and over), and A (adults 18 and older only). While some of these taxonomies differ slightly, their existence and ubiquitous and voluntary use refutes notions that there is a vacuum on app ratings or age appropriateness indicators for parents.

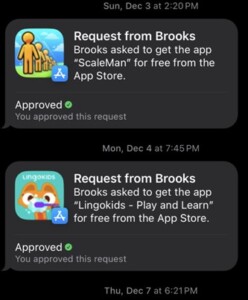

Notifying parents. When a parent sets up their child’s smart device, they can indicate the child’s birthdate and configure the device’s settings to enable control over aspects of the device’s use, including by limiting access to certain apps, switching off access to browsers, and imposing time limits on usage. Importantly, this process doesn’t involve the app store verifying the age of the child. The process is entirely in the hands of the parent, who holds the key and is either accurate or not about the child’s age, according to their preferences as a parent. The key is that the child’s identifier is associated with the parent’s, by virtue of the option to add the child as a Family member in the parent’s own operating system settings. Having traversed these steps, the parent can configure the categories of apps that are off limits for their child, unless they approve the download via text. Here’s what it looks like to receive a notice from the child’s device and approve the request:

If you watched any of the playoff games this past weekend and saw an ad calling for legislation to require parental notice, you might have pictured such a bill to require something a lot like this. Good idea, you might’ve thought, and maybe you assumed that if a bill is necessary, it must be because it doesn’t happen now. But as you can see, this is how it looks, and it works well.

How would a new federal parental notice regime lead to problems? The mechanisms in place to effectuate parental notice of app downloads or purchases aren’t perfect, but they actually work. There are three main issues with a federal law requiring app stores to provide parental notice:

- A mandate to verify age would be unconstitutional. If a mandate for app stores to provide parental notice involves a requirement to verify the age of every individual (including, necessarily, adults) using the app store, the requirement would not survive a First Amendment challenge. Previous efforts to require age verification have been struck down because, as one appeals court put it, such verification mandates would “require adults to relinquish their anonymity to access protected speech” on the internet. It is not worth Congress’ time nor the courts’ precious resources to relitigate a mandate that is impermissible under the First Amendment and unnecessary given the tools currently available to parents.

- Congress and regulators as parent. Currently, a key pillar of parental notice facilitated by app stores is parents’ ability to set the parameters for notice. For example, I recently allowed my son to download a game for the 6 – 8 age group even though he was still 5 for another 2 weeks. My wife and I tested it out and determined it was okay for him to play for short periods of time, so I override my own default setting temporarily to enable him to request my permission, and I approved the download. In statute, there could be allowances for “reasonable parental overrides” or however negotiators might draft such an exception, but the problem with legislating on this is fundamental. Parental decisions on these issues are fact-specific, and the right call may be different from one set of parents to another. The ability to adhere to what a regulator might think of as the most appropriate decision for their child may also be dependent on parents having the resources to meet those public official expectations. For example, most parents likely do not have the resources to buy their children the latest and greatest smart devices and may share devices with their children. In these common cases, statutory regimes dependent on the existence of a separate device or digital identity would apply awkwardly and likely force noncompliance. Ultimately, a statutory requirement for app stores to provide notice in circumstances outlined by Congress takes decision making currently in the hands of parents and places it in the hands of government.

- Clunkier design. Currently, app stores enable parental notice based on how parents set up their child’s device. The app store can improve the methods and mechanisms used to effectuate this notice and execute the parent’s decision to allow or disallow a download with each update. Under current conditions, consumer experience and feedback expressed through the market mechanism drives the design. Congress has an opportunity to make this feedback loop much worse and more convoluted by interjecting a layer of compliance between parents and their devices. Under such a regime, instead of designing for parental control and experience, app stores would be designing for compliance. We are seeing the inevitable challenges of trying to comply with convoluted mandates unfold in real time as major platforms unveil their Digital Markets Act (DMA) compliance programs. While a great deal of effort and resources have gone into these compliance regimes, developers have a lot of information to sift through. Just as DMA addresses priorities of regulators rather than developers or consumers, in this case, a parental notice regime would require app stores to meet regulator expectations rather than parents.

Regardless of whether the app store notice idea takes off, it is clear that interest in ideas like it will continue. Parenting is not easy, especially now that kids have online identities. It would be a shame if Congress were to make it even harder by checking our IDs at the door, binding our devices in red tape, and confiscating our choices as parents.