As the App Association launches our new Amplify Diverse Talent Working Group, the first set of issues we are examining are those that influence access to capital for entrepreneurs of color. We recently convened leaders in the space for our first Amplify Diverse Talent webinar “Access to Capital: The Issues,” with a second webinar, “Access to Capital: Solutions,” scheduled for next month.

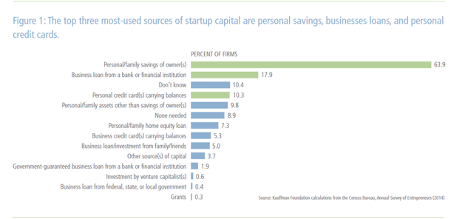

As panelists in the first webinar pointed out, the lack of access to capital for Black and Brown entrepreneurs is a symptom of larger, systemic racism within America. The racial wealth gap in the United States remains relatively unchanged since 1967, with Black and Brown Americans making a little more than $57 for every $100 in income earned by their White counterparts. When you consider that 66 percent of new entrepreneurs start their businesses using personal savings, that statistic becomes even more alarming.

To compound the issue, Black and Brown entrepreneurs are denied loans nearly twice as often as White entrepreneurs, limiting access to what could serve as a crucial supplementary funding mechanism.

So what protections are currently on the books for such entrepreneurs? How can developers of color protect themselves when they believe they’ve been the victim of a discriminatory lending decision?

Fair Lending Rules

When it comes to lending protections for people of color, the landscape, at least at the federal level, primarily consists of two laws—the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) and the Fair Housing Act (FHA) — both of which prohibit discrimination in credit transactions, including transactions related to residential real estate. For the purposes of this blog, we will focus on ECOA, which is the more relevant law to the app developer community.

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act was enacted in 1974 and is detailed in Title 15 of the United States Code. The act states that individuals applying for loans and other credit can only be evaluated using factors that are directly related to their creditworthiness. This protection prohibits lenders from considering consumers’ race, color, national origin, sex/gender, religion, marital status, age, or their receipt of public assistance when evaluating an application or determining the conditions of the loan, such as the interest rate or other fees. Often creditors do ask applicants to share this information during the application process, but they are forbidden from using it as the basis for denial of credit or to inform the terms specified in the credit offering.

Under the law, “creditor” is defined as any organization that extends credit, including banks, small loan and finance companies, retail and department stores, credit card companies, and credit unions. It also applies to anyone involved in the decision to grant credit or set its terms—for example, a loan officer.

How are App Developers Protected?

Any app developer who applies for a loan from a traditional creditor, such as a bank or credit union, would be protected under ECOA. Generally speaking, that means that the creditor would be legally barred from profiling the app developer and declining to provide them credit on the basis of a personal characteristic, such as their race or gender.

From a legal standpoint, an app developer who believes they have been discriminated against in a way that contravenes the protections under ECOA has several avenues by which to prove that discrimination. In determining the existence of lending discrimination, the courts have traditionally recognized three types of proof under ECOA: overt evidence of disparate treatment, comparative evidence of disparate treatment, and evidence of disparate impact.

Each of these standards carries different evidentiary burdens for proving the discriminatory action. Overt evidence of disparate treatment occurs when the lender openly discriminates on the basis of protected characteristics alone, for example by charging increased interest rates for women. Overt evidence of disparate treatment would also occur when a lender discourages an applicant from applying for a loan on the basis of a protected characteristic, even if they do ultimately provide the loan.

Comparative evidence of disparate impact occurs when a lender treats similar applicants differently on the basis of a protected characteristic, for example by failing to extend a loan to a minority individual with the same or similar creditworthiness of a non-minority individual who did receive a loan.

Finally, evidence of disparate impact can also occur when a lender’s policies are facially similar for all creditors, but whose policies have the impact of denying individuals with protected characteristics from receiving credit.

The protections supplied by ECOA represent a significant protection for app developers of color. After all, behind personal or family savings, bank loans constitute the second most common source of capital for startups. Though that number lags for people of color compared to Whites, bank loans still constitute the primary source of funding at least 15 percent of the time for those groups.

Source: https://www.kauffman.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ase_brief_startup_financing_by_race.pdf

That said, there remains both a funding and loan denial gap when comparing White and Black applicants. Furthermore, federal agencies tasked with overseeing ECOA have been reticent to prioritize aggressive enforcement of the law. For example, with the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, Congress amended ECOA to require that financial institutions collect and report information concerning credit applications made by women- or minority-owned businesses and by small businesses, which could help uncover systemic patterns of discrimination. Although the agency tasked drafting rules to implement this amendment, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), has implemented many other rules from Dodd-Frank, it has yet to for this one. In fact, it didn’t even begin to flex its rulemaking powers in this area until 2017, when it released a broad report about the small business lending market, with no further action until November 2019, when it held an information-gathering symposium on the topic.

What About Other Types of Funding?

Obviously, startups raise capital in many other ways outside of traditional bank loans. Venture capital (VC), for example, can be an attractive option, though the representation and funding gap for minority populations in venture capital is staggering. As of 2018, venture capital firms employed less than 3 percent Black and Latinx individuals as a share of all employees. Moreover, only 1 percent of VC funding went to Black-owned companies, while only 0.2 percent of VC funding went to companies led by Black women.

So, do ECOA protections extend beyond traditional bank loans? Unfortunately, most of the time, the answer is no. Venture capital investment firms, for example, are not typically regulated in the same way that most traditional banks and credit unions are and operate in ways that differentiate them from traditional creditors under ECOA. Rather than issuing loans with the expectation of repayment, VCs typically seek equity stakes in the companies in which they seek to invest. While other rules, including state anti-discrimination law, may apply, they are seldom enforced to their full capacity.

Some traditional financial institutions do issue what is called “venture debt financing” to certain venture capital-backed startups, which is typically structured as a three- to four-year term loan or equipment lease. Obligations under ECOA would indeed pass through in this instance. However, many other non-bank players also offer venture debt financing and may not be covered by ECOA.

App developers at the startup stage might also look to government, particularly the Small Business Administration (SBA) to help them secure a loan under their 7(a) loan program. Historically, SBA has helped small businesses gain greater access to capital by guaranteeing a portion of the amount borrowed, capping interest rates, and limiting fees. SBA 7(a) loan applicants would be covered under ECOA.

Conclusion

While existing lending protections for developers and entrepreneurs of color are clearly a mixed bag, it is important for one to know their rights and avenues of recourse, in addition to noting the areas that need improvement over current law. The federal anti-discrimination laws that apply in traditional lending markets are theoretically substantial, yet those protections leave much to the individual and require much stronger agency enforcement, as well as enhanced data gathering to better paint a picture of market abuses. Moreover, developers should be aware that many protections lapse when they leave the traditional funding market for the equity world, where funding gaps are at their starkest. Stay tuned to future output from our Amplify Diverse Talent working group as together we seek to shed light on these and other thorny issues, raising the voices of those in the developer community who best understand their real world impact and can direct us towards empowering solutions.