The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is at the center of a hearty discussion about ways to leverage electromagnetic spectrum to bridge America’s digital divide. Today, several spectrum bands remain unlicensed and underutilized while more than 34 million Americans do not have access to fast broadband or the benefits and efficiencies it brings. To understand why the spectrum debate is so contentious, we must unpack the history of spectrum and the events that made it such a coveted resource. History tends to repeat itself, and telecommunications providers and innovators must address challenges within the debate to better serve Americans across the country.

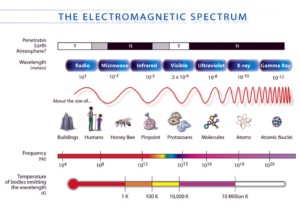

Electromagnetic spectrum refers to the bands of airwaves or radio frequencies used to carry various types of communications. Spectrum provides the necessary pathway for today’s wireless communications, including wi-fi and LTE. The full range of spectrum spans from extremely low-frequency waves used in undersea communications to high-frequency gamma rays. The most frequently used spectrum is radio spectrum, ranging from 3 kilohertz to 300 gigahertz, and it serves as the foundation for everything from consumer mobile wireless services to astronomy satellites.

Why is Spectrum So Special?

Much like real estate, spectrum is a vital, limited resource. Only one “tenant” can use a spectrum frequency at a time, and each frequency has different characteristics and serves unique purposes. For this reason, spectrum bands are incredibly valuable. In fact, the 645.5 megahertz of licensed spectrum that supports wireless devices is estimated to be worth a massive $455 billion. It is no surprise that private businesses, industry groups, and government agencies continue to debate the best utilization of unused, unlicensed spectrum bands in the United States. Many of the bands lie fallow due to disagreement over their allocation and use, but everyone agrees that unused spectrum cannot benefit Americans who cannot access it. To understand the contentious fight for unlicensed spectrum bands, let’s explore its history.

More than a century ago, Reginald Fessenden became the first voice Americans heard over broadcast radio when he read Bible verses and played “O Holy Night” on the violin in 1906. After several years of exploring this newfound channel for communication, it became clear that competing broadcasts on the same frequencies could create interference and, in extreme cases, tragedy — in 1912, the Titanic’s radio distress signal was garbled by interference from neighboring ships, delaying the rescue of passengers. Later that year, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1912, establishing government management of spectrum and setting forth the first licensing system for airwave use. Ever since, U.S. policies have enabled the federal government to utilize a command-and-control system to determine the users, and uses, of spectrum airwaves.

Fifteen years later, the uses for spectrum by licensees enabled not just the broadcast of sound, but also of image and video. In 1927, Philo Taylor Farnsworth was the first to utilize an electronic television to successfully broadcast video over spectrum, though it would take several years before the federal government re-purposed airwaves to allow consumers to enjoy television broadcasts.

Today, a variety of industries use several spectrum airwaves throughout the country, but the United States is still home to many unlicensed, underutilized frequency bands. Powerful actors within the communications ecosystem continue battling over these valuable spectrum bands to support legacy technologies and business models. Their fights to gain, or retain, control over spectrum bands ultimately jeopardize the ability to leverage available spectrum for new, innovative, beneficial uses.

Can’t We All Have a Piece of the Pie?

The FCC manages spectrum, and it is responsible for licensing available bands to entities that wish to use it. While the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) regulates federal agencies’ use of spectrum, the FCC oversees the allocation of spectrum for the private sector and ensures that the spectrum is used in the “public interest, convenience and necessity.” As the public’s gatekeeper for spectrum, the FCC fields petitions from any non-government entity that wishes to use spectrum in a novel, innovative way.

Given the value of this limited resource, it is easy to predict fights between competing interests over spectrum uses and frequency allocations. Telecommunications industries driven by legacy technologies have long fought to prevent changes to the frequency allocations that would ultimately introduce new competitors into the ecosystem.

Take the story of inventor Edwin Howard Armstrong, who invented the Frequency Modulation (FM) radio in 1933. Armstrong’s innovation provided a more efficient way to transmit sound over the airways than the more established, legacy Amplitude Modulation (AM) radios. Leading experts agreed that FM transmissions were superior to their AM counterparts, but lobbyists for the AM radio industry fought against this new innovation, flooding the FCC with reports opposing the new technology that threatened their market share. As a result of the coordinated push-back, it took nearly a decade before the FCC granted spectrum licenses to FM radio companies, and they soon replaced AM radios as the dominant player within the market. The new technology proved to be so efficient that the U.S. Army used FM radios to supplement radio communications in World War II – even General George S. Patton’s Third Army used FM radios while storming through France in 1944 because wireline communications were unable to keep up with their pace.

The same dance occurred for America’s first television broadcasters, whose initial movement into the telecommunications ecosystem was challenged and delayed by legacy radio interests. For years, radio broadcasters – first AM, then FM – maintained control over the market and were not eager to share spectrum allocations with this new, disruptive entity. For this reason, America’s first television broadcast took place in 1941, more than a decade after the British Broadcasting Company (BBC) began providing regular television broadcasts to the public.

Following this trend, it is no surprise that the mobile phones introduced to consumers in the late 1980s were first launched as a mobile telephone service (MTS) four decades earlier. In 1946, engineers recognized that the characteristics of the spectrum used for television broadcast were even more hospitable to the long-range, two-way wireless communications vital to mobile telephones. Inevitably, television broadcasters pushed back. When AT&T petitioned the FCC to re-purpose already available spectrum airwaves for MTS in 1947, the FCC declined. They stated that the mobile telephone service was not in the “nature of convenience or luxury” and maintained the spectrum for legacy users like radio and television broadcasters. Instead of re-purposing some of the available spectrum for mobile telephone use, the FCC kept it tagged as broadcast-only. This ultimately left available spectrum bands unused by the broadcasters that licensed it, as well as the mobile telephone service providers that wished to leverage it in a new way. With a 40 year wait for mobile phone technologies, consumers were the biggest losers.

Looking to the Future

These examples reflect a greater trend throughout the history of spectrum –legacy technologies guard available spectrum to the detriment of innovators seeking new uses of spectrum. The interests of existing market players have long outweighed the efforts of entities looking for new benefits for consumers.

Today, we are faced with an opportunity. To avoid repeating history, public interest must prevail in the determination of spectrum allocations for new uses in innovative industries. Unlicensed, available spectrum bands can be utilized to help Americans on the wrong side of the digital divide. We encourage the FCC to allocate unused television spectrum bands, or television white spaces, to new entities that can bring broadband connectivity to the millions of Americans who need it most.

Failure to learn from our past mistakes will only hurt our ability to innovate and Americans’ opportunity to benefit and grow.